Chapter 6 - Monoids and Monads

In this lesson we will learn about two new design patterns: Monoids and Monads. Both of these patterns will allow us to do chaining effectively.

6.1 Monoids

Monoids are functions that combine things using a binary operation that have the following properties:

- Closure - When we combine two things with our function, we always get something of the same type.

- Associativity - When we can combine more than two things, it does not matter which two things we combine together first. Mathematically this is written as \((A + B) + C = A + (B + C)\). It is important not to confuse this with the commutative property which allows you to change the order like \(A + B = B + A\). Monoids do not need to satisfy the commutative property.

- Identity - There is always something we can combine with that will return the original value using our function.

In programming, we have already used monoids several times including:

- Adding numbers

- Combining Strings

- Combining Lists

Frequently the following operators are monoids: \(+\), \(++\), \(*\), \(\land\), \(\lor\)

Due to the closure property, we are able to combine things easily with our functions using chaining because the input and output interfaces are compatible. Due to the associative property, we can divide the work up into individual combinations and even use threading to complete them in parallel using multiple processors. Due to the identity we can deal with special cases such as adding to nothing or appending to an empty list.

As an example, we will rewrite the ability to combine (i.e. concatenate) two lists. Notice in the definition below we are purposefully not using \(++\) because this combine_list function is actually trying to implement \(++\).

\(spec ~ ~ combine\_list :: [a] ~ ~ [a] \rightarrow [a].\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_list :: []~ ~ List \rightarrow List;\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_list :: List ~ ~ [] \rightarrow List;\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_list :: [First|Rest] ~ ~ List2 \rightarrow [First | (combine\_list ~ ~ Rest ~ ~ List2)]\)

\(\nonumber\)

The first part of the definition provides support for the identity property. Observe that this function can be chained together in different pairs (associative property) and the result is the same.

combine_list(List, []) -> List;

combine_list([], List) -> List;

combine_list([First|Rest],List2) -> [First | combine_list(Rest, List2)].

test_combine_list() ->

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] = combine_list([1,2,3], [4,5,6]),

% Test Associate Property

L1 = [1, 2],

L2 = [3, 4],

L3 = [5, 6],

% L1 and L2 first, then L3

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] = combine_list(combine_list(L1, L2), L3),

% L1 with the result of L2 and L3 done first

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] = combine_list(L1, combine_list(L2, L3)),

ok.Since we are combining things, monoids frequently work well with a fold. Notice that the lambda function in the fold below has to account for the different order of parameters between the foldl and the combine_list functions. In the future we will write our data structures functions such that the order is the same.

test_combine_list() ->

L1 = [1, 2],

L2 = [3, 4],

L3 = [5, 6],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] = lists:foldl(fun (Value,Acc) -> combine_list(Acc,Value), [], [L1, L2, L3]),

ok.Comparing with other languages, monoids should seem familiar to operator overloading or overriding. The ability to define what it means to perform an operator on anything. While Monoids are restricted primarily to combining operators, the principle of closure is still important. For example, consider a function that combines two accounts. Each account is defined by an owner, an identifier, and a balance. We could write a function that does the following:

\(struct ~ ~ account ~ ~ \lbrace string:Owner, string:Identi\mathit{f}ier, real:Balance \rbrace.\)

\(spec ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: account ~~ account \rightarrow real.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: Account_2 ~~ Account_1 \rightarrow Account_1.Balance + Account_2.Balance.\)

\(\nonumber\)

However, with this definition, we don’t have closure since our inputs are Accounts and our output is a real number. When developing a monoid, it is important to return a compatible type. In this case, when we combine the accounts, we should return an account. In our example below, we will choose to keep the owner and identifier from the account that had the highest balance when recreating our Account (which we are representing by a tuple of size 3).

\(struct ~ ~ account ~ ~ \lbrace string:Owner, string:Identi\mathit{f}ier, real:Balance \rbrace.\)

\(spec ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: account ~~ account \rightarrow account\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: Account_1 ~ ~ nil \rightarrow Account_1;\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: nil ~ ~ Account_2 \rightarrow Account_2;\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: Account_1 ~~ Account_2 \rightarrow\)

\(\quad \quad \lbrace Account_1.Owner, Account_1.Identi\mathit{f}ier, Account_1.Balance + Account_2.Balance \rbrace ~ ~\)

\(\quad \quad \text{when} ~ ~ Account_1.Balance \ge Account_2.Balance ;\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ combine\_accounts :: Account_1 ~~ Account_2 \rightarrow\)

\(\quad \quad \lbrace Account_2.Owner, Account_2.Identi\mathit{f}ier, Account_1.Balance + Account_2.Balance \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

Problem Set 1

Starting Code: prove06_1/src/prove06_1.erl

- Implement the

combine_acountsfunction as described above. - Modify

combine_accounts_2_testto use afoldlto demonstrate the ability to combine 5 accounts. Use the test code provided in the starting code. - A monoid can be used to combine anything. In a functional language, that includes functions. Write a monoid that combines two functions of arity 1. Call your combination function

combine_functions. Remember thatcombine_functionsmust satisfy the closure property which means that it must also return a function with arity 1. It should also satisfy the identify property (combine a function withnil).

- Modify

combine_functions_2_testto use afoldlto combine all three functions together from the previous problem. Use the test code provided in the starting code.

6.2 Monads

When we consider the closure property we saw with the Monoid, it may not always be practical to have the data types be consistent between inputs and outputs. Some functions may need to return additional data (i.e. meta-data) which is of a different type. A Monad is a type that contains additional meta-data that is part of strategy to simplify or generalize our software. This meta-data can be used for several purposes including saving error and state information.

A common Monad seen in software is called the Maybe. A Maybe type is a tuple of size 1 or 2. The first value in the tuple is either ok or fail. The second value is an actual value (or result) and is only provided if the first value was ok. We call the ok or fail meta-data. Meta-data is information that describes our primary data.

In this example, the use_inventory function will return a Maybe. The result will be ok if there was inventory available to use and it will return fail if there was no inventory available. The meta-data ok and fail describe the inventory value.

\(struct ~ ~ maybe\)

\(\quad \quad \lbrace atom(ok), a:Value \rbrace ~ ~ or\)

\(\quad \quad \lbrace atom(fail) \rbrace.\)

\(spec ~ ~ use\_inventory :: integer \rightarrow maybe\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ use\_inventory :: Inventory \rightarrow \lbrace fail \rbrace ~ ~ \text{when} ~ ~ Inventory == 0;\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ use\_inventory :: Inventory \rightarrow \lbrace ok, Inventory - 1 \rbrace .\)

\(\nonumber\)

Here is the code implementation for our use_inventory function:

use_inventory(Inventory) when Inventory == 0 -> {fail};

use_inventory(Inventory) -> {ok, Inventory - 1}.In this example, use_inventory returns a Maybe instead of a number which means we don’t have closure which affects our ability to chain properly. Monad types include helper functions to adapt the output of a function (i.e. Maybe) to the input of a function (i.e. number). Each Monad must include a type constructor (often called unit) and a bind function described below.

The type constructor will provide a way to create a Monad type using a given value. Here is the type constructor for our Maybe type:

\(spec ~ ~ maybe\_unit :: a \rightarrow maybe.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ maybe\_unit :: Value \rightarrow \lbrace ok, Value \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

Here is the code for the Maybe type constructor:

The bind will provide way to apply a function to a Monad type. The functions that support our Monad type don’t take a Monad type as the input. For example, our use_inventory takes a simple Inventory value. The output of the use_inventory is the maybe type. The bind will convert the output maybe type into the simple Invetory value that use_inventory is expecting.

If the Maybe is ok, then the bind will extract the value and apply it to the function. Note that the return of the function will be a Maybe again. If the Maybe is fail, then it will not run the function but instead just return a maybe showing fail. The bind function will manage the meta data of ok and fail in our Monad. The use of the bind function allows us to chain functions that return the Maybe Monad type. Here is the bind definition. Notice that the \(\lambda\) is monadic in that it returns (but does not receive) a Monad type.

\(spec ~ ~ \lambda :: a \rightarrow maybe.\)

\(spec ~ ~ maybe\_bind :: maybe ~ ~ \lambda \rightarrow maybe.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ maybe\_bind :: \lbrace ok, Value \rbrace ~ ~ \lambda \rightarrow (\lambda ~ ~ Value);\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ maybe\_bind :: \lbrace fail \rbrace ~ ~ \lambda \rightarrow \lbrace fail \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

Here is the code for the Maybe bind:

Using our maybe_unit and maybe_bind we can chain our use_inventory function.

test_maybe() ->

{ok, 8} = maybe_bind(maybe_bind(maybe_unit(10), fun use_inventory/1), fun use_inventory/1),

{fail} = maybe_bind(maybe_bind(maybe_unit(1), fun use_inventory/1), fun use_inventory/1),

ok.For each Monad we create, we may need one or more bind functions to provide the proper support for the unique meta data in our Monad. In the problem set below, you will write a bind function that will combine meta data from previous bind executions. Additionally, in the problem set you will simplify the chaining by using a foldr.

Problem Set 2

Starting Code: prove06_2/src/prove06_2.erl

- Write a function called

cut_halfwhich will divide a number by 2 and returns aMaybe(as defined above) with an integer (not floating point) answer. If the remainder after division is not 0 (i.e. fractional) or if the number was less than or equal to 1, then theMaybeshould indicatefail. Implement themaybe_bindandmaybe_unitfunctions above. - We will define a Monad called

Resultwhich is either{ok}or{error, List of Error Messages}. You will use thisResultMonad to perform checks on a password. Thecheck_mixed_case,check_number_exists, andcheck_lengthfunctions provided to you already use thisResultMonad type. Notice that each function returns a list of size 1 when anerroris returned. You need to write theresult_unitandresult_bindfunctions. The bind function should save all previous reasons in the Result. For example, if the password provided to these functions was “simple”, and you chained together all 3 checking functions, then thebindwould result in anerrorresult containing a list of all 3 error strings. Use the code in the template for testing. - Modify the

result_2_testto chain the bind functions together using alists:foldrinstead.

6.3 List Monad

In a few weeks we will begin our exploration of data structures within a functional language. Reflecting back earlier in the semester, we saw how the list was used in Erlang. One thing that we have not yet explored is how to implement a length function for our list. Even though Erlang has a built-in length function which is good to always use, implementing the length can be a good example for exploring the Monad further.

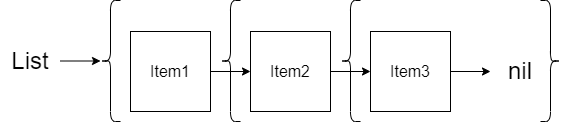

Before we look at the Monad, we are going to define our lists a little bit differently from previous weeks. Instead of using the built-in list data type in our languages, we are going to create our list completely from scratch. Doing this will prepare us for the data structures we will see in the future.

Let’s define a list using tuples:

- Empty List:

nil - One Item List:

{Item1, nil} - Two Item List:

{Item1, {Item2, nil}} - Three Item List:

{Item1, {Item2, {Item3, nil}}}

The first item in each tuple represents the value in the list and the second item in the tuple represents the remainder of the list. This is very similar to the \([First|Rest]\) format we often write where \(First\) represents the first value in the list and the \(Rest\) represents the remainder of the list.

\(struct ~ ~ list ~ ~ \lbrace a:First, list:Rest \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

For simplicity, we will define a push and pop function which will only affect the front of our list.

\(spec ~ ~ push :: a ~ ~ list \rightarrow list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ push :: Value ~ ~ List \rightarrow \lbrace Value, List \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

\(spec ~ ~ pop :: list \rightarrow list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ pop :: nil \rightarrow nil\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ pop :: \lbrace First, Rest \rbrace \rightarrow Rest.\)

\(\nonumber\)

Implementing this code we have the following:

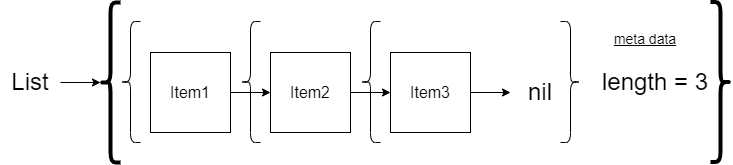

If we wanted to calculate the length function, we would need to visit every item in our list to count. To avoid this, we can store the length as meta-data using a Monad. We will define our list Monad type to be: {List, Length}. Using this type, our example lists now look like this:

- Empty List:

{nil, 0} - One Item List:

{{Item1, nil}, 1} - Two Item List:

{{Item1, {Item2, nil}}, 2} - Three Item List:

{{Item1, {Item2, {Item3, nil}}}, 3}

Recall that Monad functions don’t take the Monad type as an input but they should return the Monad type. That will mean that when we call our push and pop functions, the length must be stripped off. How does the push and pop know what to set the length to in the result? Remember that the bind function is responsible for managing the meta data. We will have the push and pop return a delta length. For push, the delta length will be positive 1 and for pop, the delta length will be negative 1. We will have the bind manage the length meta-data.

In our specifications and definitions below, we will modify the push and pop to use the Monad type and also include the type constructor (in this case we will use a more interesting name like create instead of unit) for creating an empty list (length of 0) and the binding function. Since we will want the ability to see the list and length independent of the Monad type, we will provide some simple helper functions (value and len) for these as well.

The bind will be more complex because it will need to handle both push and pop functions which have different arity. The \([a]\) (called Optional_Parameters in the definition) contains the variable number of parameters to pass to push and pop. We will use a traditional Erlang list data structure to store these parameters.

\(struct ~ ~ list ~ ~ \lbrace a:First, list:Rest \rbrace.\)

\(struct ~ ~ m\_list ~ ~ \lbrace list:List, integer:Length \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

\(spec ~ ~ push :: a ~ ~ list \rightarrow m\_list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ push :: Value ~ ~ List \rightarrow \lbrace \lbrace Value, List \rbrace, 1\rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

Notice in the pop funciton below, we are reusing our create type constructor for convienance.

\(spec ~ ~ pop :: list \rightarrow m\_list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ pop :: nil \rightarrow (create);\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ pop :: \lbrace First, Rest \rbrace \rightarrow \lbrace Rest, -1 \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

\(spec ~ ~ create :: \rightarrow m\_list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ create :: \rightarrow \lbrace nil, 0 \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

Recall that only our push function has an additional value parameter. If pop is called, we would expect our Optional_Parameters to be an empty list. We have generalized our \(\lambda_{bind}\) to take a list of optional parameters which potential could be empty. We will use the Erlang function apply to pass these optional parameters to match our push and pop specifications previously given above.

\(spec ~ ~ \lambda_{bind} :: [a] list \rightarrow m\_list.\)

\(spec ~ ~ bind :: m\_list ~ ~ \lambda_{bind} ~ ~ [a] \rightarrow m\_list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ bind :: \lbrace List, Length \rbrace ~ ~ \lambda_{bind} ~ ~ Optional\_Parameters \rightarrow\)

\(\quad \quad \lbrace New\_List, Delta\_Length \rbrace = (\lambda_{bind} ~ ~ Optional\_Parameters ~ ~ List),\)

\(\quad \quad \lbrace New\_List, Length + Delta\_Length \rbrace.\)

\(\nonumber\)

\(spec ~ ~ value :: m\_list \rightarrow list.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ value :: \lbrace List, Length \rbrace \rightarrow List.\)

\(spec ~ ~ len :: m\_list \rightarrow integer.\)

\(de\mathit{f} ~ ~ len :: \lbrace List, Length \rbrace \rightarrow Length.\)

\(\nonumber\)

When implemented, you will need to use the apply function in Erlang to handle passing the List and Optional_Parameters to the \(\lambda_{bind}\) function. If push is used, then the Optional_Parameters will be a one element list containing the value to push. If pop is used, the Optional_Parameters will be an empty list. Some of these functions are implemented below and some are left as an exercise.

push(Value, List) -> {{Value, List},1}.

% pop is left as an exercise

create() -> {nil, 0}.

bind({List, Length}, Function, Optional_Parameters) ->

LEFT FOR AN EXERCISE

len({_List, Length}) -> Length.

value({List, _Length}) -> List.For the length get updated, we have to use the bind function as shown in the test code below.

L1 = create(),

L2 = bind(L1, fun push/2, [2]),

L3 = bind(L2, fun push/2, [4]),

L4 = bind(L3, fun push/2, [6]),

L5 = bind(L4, fun pop/1, []),Problem Set 3

Starting Code: prove06_3/src/prove06_3.erl

- Implement the

popandbindfunction with the list Monad type. Use the code in the template to test. Note that theapplyfunction is available in Erlang which will call a function and pass a variable list of arguments to the function.

::::